Beekeeping - The Basics

'Bees haven't read the Rules!'

There are a few things to know about honey bees before you get started keeping them, learning the basics will save you time, money, disappointment, failure, injury, and of being put off! Fortunately for us our native honey bees are mostly creatures of habit, with a range of predictable behaviours, and once you know and recognise those behaviours its much easier to keep them, and keep them healthy and productive. They will however confound you just when you are least expecting it. Despite all that you will read about beekeeping, honeybees simply follow the seasons' variations, the weather and the availability of forage, the triggers that control the different aspects of their life cycle. Our seasonal beekeeping calendar, although generally attributed to certain months of the year, has to be viewed as variable and that it follows the changes in climate which control the beginning and end of each season, and that could be several weeks earlier or later than we might expect. Adding to that unpredictability, the bees haven't read our beekeeping books and rules either, and will do their thing when they decide the time is right. All the keeper has to do is be vigilant enough to spot the signs, and be knowledgeable enough to recognise them and what action, if any, is required.

Colony health will be the main focus of your beekeeping, and if they are kept healthy they will thrive and repay your efforts tenfold. It follows that health and safety (theirs and yours) is always first and foremost of what ever you are going to do in beekeeping. Getting up to speed with the various honeybee pests and diseases, how to identify and treat them is essential and will take the most time to learn. Help and support to manage this can be found in the easy to read pages of information and sources of further information in the Diseases section of this website. Use the dropdown menu to select specific diseases, their detection and management.

Honeybee Products

Humans have recognised the potential of honeybee products since Neolithic Times, with the early farmers keeping and exploiting them for their honey stores. Today the attractions are the products the bees create and store in the hive namely: honey; pollen; wax; royal jelly; and propolis, and their main uses are for food, cosmetic and medicinal purposes.

Honey - the sweet food created from nectar and enzymes and stored over the summer by honeybees for winter use. It has been used for centuries as a natural sweetener, having been found in archaeological artefacts from ancient civilisations such the Egyptian tombs. Containing virtually no fats, protein or fibre, it is increasingly popular as a natural and largely organic sweetener in today's health conscious society. Due to its viscosity and low moisture content honey has some very interesting and useful properties as an antibiotic, dressing wounds in honey makes it impossible for bacteria to survive, and the bioactive plant compounds and antioxidants it contains further enhances its medicinal benefits.

Beeswax - the main building material created by honeybees from special glands has similarly been prized over the centuries as a useful material, ancient Egyptians using it in the embalming process, for creating air-tight seals, as an early preserve on wall writings, and in the lost wax casting technique for making jewellery. It also makes a very clean burning source of light, and makes excellent candles. It was widely used in this respect and was often reserved almost exclusively for the Christian Church. This tradition continues today with a high percentage of beeswax used in Church candles. Today bees wax is used extensively used in cosmetics, medicines and in furniture and leather care products.

Pollen - the powdery male reproductive component of flowering plants gathered by honeybees as source of nutrient for feeding their larvae, has in recent years become important in the health care market because it’s loaded with nutrients, amino acids, vitamins, lipids and a wealth of active substances, making it a highly valued for use as a health food supplement.

Propolis - is a mixture of natural plant / tree resins which bees collect essentially to stick things together, strengthening the hive, stopping up small holes and cracks in their nests, and acting as an antiseptic. These strong antiseptic properties make it medicinally useful for creating tinctures, and has been used in medicine since the Ancient Greeks discovered its beneficial effect in treating abscesses, tumours and wounds.

Royal Jelly - is the special food fed to young bees and young queen bees in particular. It is a highly concentrated mixture of proteins, sugars and free amino acids which is produced by worker bees using their hypopharyngeal gland. It is used as a health food and cosmetic, although most benefits to humans are conjecture and not scientifically proven.

Bee Venom - continues to be studied in detail for various medicinal purposes. It is a highly complex mixture of chemicals, containing anti-inflammatory and inflammatory compounds, enzymes, sugars, minerals, and amino acids. It is used in venom immunotherapy and in treating a number of medical conditions including arthritis, neuralgia, multiple Sclerosis, tendonitis, fibromyositis and enthesitis

Honeybee Biology

The Honeybee (Apis mellifera mellifera) has been native to our islands since the last ice age. They belong to the Phylum - Arthropods, a large group of invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, segmented body and paired appendages. They are Classified as Insects, having a chitinous exoskeleton, three segments to their body (head; thorax; and abdomen), three pairs of jointed legs, compound eyes, and a pair of antennae, and are closely related to sawflies, wasps and ants, all belonging to the Order - Hymenoptera. Our truly native species is sometimes referred to as the 'black bee' on account of its dark colouring and are much favoured by beekeepers who have them. Unfortunately their populations were largely decimated in the early 20th century by an imported virus to which they had no defence (Isle of Wight Disease). It is thought there may still be feral populations of the native bee still around, however it is only through microscopic examination of wing structure that their identity can be reliably ascertained. There are other commonly found variants of this bee in the UK today which come from cross breeding with other mellifera species (e.g. Italian bees which have a yellowness about them). They are all good, and are immensely important across the world as pollinators helping sustain nature and benefiting food production. What follows is common to all our mellifera species.

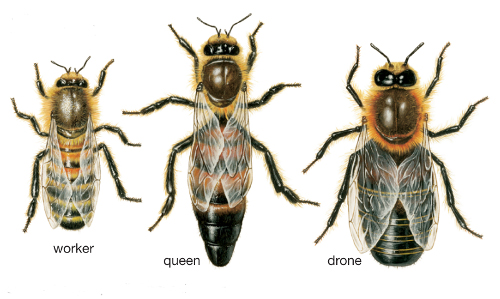

Castes - there are three castes of the honeybee – worker, drone, and queen.

Castes showing relative size: left - Worker (infertile female 10-15mm); center - Queen (fertile female 18-20mm); right - Drone (fertile male 15-17mm).Image copyright Encyclopedia Britannica ©

Workers – these are sterile female bees that do not posses the ability to produce fertile eggs (although they can in certain circumstances lay infertile eggs which hatch into drones, more on that in the Queenless Colony page). They make up the majority of bees in the colony and are the workforce. They perform all the different duties within the hive at different stages of their lives; nursing; feeding; cleaning; guarding; building; heating; foraging etc. Their lifespan is relatively short during the summer when they are flying and working vigorously (about 4 - 6 weeks), but can survive for up to 5 months during the winter. They will forage up to two miles and more away from the hive to exploit abundant pollen and nectar sources. The workers can sting and will do if necessary, but when they do the stinging apparatus tears away from their bodies and they die shortly afterwards.

Drones – these are the male bees and are visibly larger than the workers. They do not have the ability to sting and their lifespan is relatively short depending on when and if they mate. They are easily spotted in the hive and make a distinctive droning buzz when flying, which may contribute to their name but it is more likely due to them living off the labours of the workers. Their main purpose is to fertilise virgin queens once they have become sexually mature at around 36 days from egg. They fly out (up to 7km from their hive) to perform this function in 'Drone Zones' of many hundreds of individuals, then die immediately after copulation. Their other functions in the colony are limited to heating or cooling brood, and maintaining colony moral when there is a possibility of swarming or supercedure. Their appearance in the hive is a clear indication that the swarm season for that colony has begun and it's worth making a note of the date drones appear in the nest to help plan artificial swarming or splits. They are produced mid/early spring by the colony to enable fertilisation of young queens when required e.g. at swarm time, or supercedure (more on that in the Queenless Colony page). Towards the end of the summer remaining drones will be booted out of the hive by the workers as they are then an unwelcome drain on resources, their job is done. The importance of drones in a colony however can never be overstated.

Queen – a colony will have one queen bee, a fully fertile female that can lay anything up to 1500 eggs per day! She will lay eggs, one per cell, as the colony requires even during the winter months as long as there are the necessary resources available. She only flies once or twice in her life and that is during her mating flight when she will mate with up to 15 -20 different drones, and if she leaves with a swarm. A queen having emerged from pupation at around 16 days is not sexually mature until day 23+ from egg, only then she will make her mating flight. She is tended in the hive by the worker bees who feed and clean her, and keep her warm during the winter. Unlike the workers and drones, a queen will live for 2 or 3 years or more, and will be replaced by the colony when she weakens. The queen uses pheromones to signal her presence to the colony and to convey different messages and instructions to the workforce. She also has the ability to sting but unlike the female workers she can sting repeatedly and does not leave the stinging apparatus in the victim or die afterwords.

Life Cycle - Its important to know the bee life cycle and to recognise the different castes at the different stages. The smallest and most numerous cells in the hive are for workers and stores; the slightly larger cells found in the lower areas of the brood nest are for drones; while single elongated cells are for queens. Eggs are laid by the queen in the bottom of cells that have been prepared by the workers. The queen can determine if an egg is male or female. Freshly laid eggs stand up straight in the cell, then lean on their side when ready to hatch. The eggs whether male or female hatch into larvae after 3 days. The workers feed the larvae in the open cells until full grown, they are then sealed over to allow pupation, before hatching as fully formed bees. Queen larvae are fed super food (royal jelly) to help fully develop their reproductive organs and make them into queens.

The approximate development time in days from fresh egg to emerged bee is as follows:

| Caste | Egg | Open Cell | Sealed Cell | Emergence | Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queen | 3 | 5 | 8 | 16 | 23+ |

| Worker | 3 | 5 | 13 | 21 | n/a |

| Drone | 3 | 6 | 15 | 24 | 36+ |

The Colony - A honeybee colony has a mind of its own and works as a single entity responding collectively to changes in conditions. It knows when increase or slow down brood production, where and when to forage, when to re-queen, when to swarm, and so on. This collective and often predictable behaviour can work for and against the beekeeper, vigilance is the key! The mood of the colony is all-telling. A queen-right colony (one with a healthy laying queen) that has everything it needs in the way of stores, space and general health will be a productive one and easy to work with. When things are not right the bees will be unproductive, and may be coming down the lane to greet you and escorting you back out while stinging you - a sign of an unhappy colony that clearly needs attention!

A healthy colony of honeybees during the summer will contain workers, drones and a queen and will number up to 50 -70 thousand bees. In the winter, the colony does not hibernate but will stay in the hive feeding off available stores and keeping warm. During the colder winter months colony numbers drop off considerably as the older bees die off and queen's egg laying slows down to maintaining just a small amount of brood and young bees in the hive to ensure a viable workforce for the spring. The success of this largely depends on the strength of the colony at the onset of winter and their access to stores of honey and pollen in the brood chamber through the winter. As spring arrives and the temperatures start to rise, spring flowers begin producing much needed pollen and nectar. The colony responds quickly to the change and gets to work foraging, feeding increasing numbers of brood, and building up strength again. By the time the spring is over the colony will be up to full strength, will have a good stock of spring honey, and will be ready to swarm - their way of proliferating and something the beekeeper must be ready for!

Learning To Keep Bees

Beekeeping Classes - Beekeeping Associations and communities exist in most areas and normally provide beginners classes. Ask around locally or do a quick internet search to find local beekeeping associations / organisations / individuals in your area. Theory classes or tuition normally commence at the start of the year in winter months culminating in practical sessions as the season progresses through spring into summer. Alternatively you may be able to hook up with an experienced local beekeeper and become their 'apprentice', which is a very good way to learn.

Beekeeping Literature - There are many many publications on beekeeping by all sorts of experts, and there are many organisations and associations that exist for beekeepers from one end of the country to the other. Having a good reference book is invaluable, there are many to chose from and some better than others. ‘Beekeeping, A Seasonal Guide, by Ron Brown’ is a good example of a guide to keeping honeybees successfully. It's a slightly dated publication now but is an easy to read guide and reference to beekeeping across the seasons that you can dip in and out of as required, and there are others a-plenty.

Online Information -If you prefer digital information rather than hard copy, there are countless websites all over the internet offering everything you need, and everything you have never thought of needing, and many things that you will never ever need! Rather than listing the good and the bad it's enough to say that while beekeeping is practised the world over, the information most useful to you is the advice that comes from and refers to beekeeping in your locality. I provide only a couple of links on this site to widely respected sources of UK beekeeping information, but really the best info and advice will come from your local beekeeping community.

Beekeeping Support - BeeBase is the Animal and Plant Health Agency's (APHA) National Bee Unit website which supports Defra, the Welsh Government and Scotland's Bee Health Programmes, and is a good source of bee health information and of course its inspectors who are always there to help. The Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA) is a division of the Scottish Government Agriculture and Rural Economy Directorate and provides scientific services and advice in support of Scotland’s agriculture and wider environment, and are always available to assist beekeepers with disease sample testing.

Above all, don't attempt to start beekeeping on your own, honeybees are delicate living creatures and will suffer badly in the hands of inexperience. However you learn, it is best to know where help can be found and to have access to a seasoned beekeeper for mentoring support, advice, and an expert eye. It will take two or three years or more of learning experience to gain a sufficient level of competence where you can work confidently with your own bees.

A beekeeping masterclass - the late Bob Simpson demonstrating to seasoned beekeepers how it can be done after many years of experience. Sharing best practice means a good get-together, and is always worth while.

It is very easy to become completely baffled and bamboozled by the great technical and scientific detail and range of techniques and advice offered by all manner of 'experts'. In truth, honeybees have existed quite happily over the millennia without human interference, they have evolved to be perfectly capable of looking after themselves in their own native environment, and their basic needs are simple. The difficulties arise generally with human intervention and activity, especially when we decide to import non native species, and keep colonies of honeybees inside man-made hives, in locations that we have chosen, and in a manner that suits our needs, rather than some cosy nuke the bees have chosen themselves because they know what suits their needs. As soon as we hive them they become our 'livestock' and we have a duty and responsibility to look after them, and we must know how to do that properly.

Getting bees - once you have learned and know the basics, organised a mentor, and somewhere to keep bees, and hives to house them in, it will be time to get bees. They can be purchased from suppliers as packages of queen and attendant workers, or as a nuc, or as a full hived colony, and you will pay accordingly. Alternatively and by far the best way of all is that if you are patient you'll be able to get a swarm or nuc from a fellow beekeeper locally as the season permits, and is often a favour that can be returned at a later date.

Honeybee Queens and Packages - Importation of queen bees and packages from outside the UK is greatly discouraged in order to prevent importation of unwanted material, pests and disease. It is the responsibility of the beekeeper to ascertain the source of queens and packages they intend buying and of the pertinent regulations.

Somewhere To Stay

Location, location, location! We keep our bees in hives, artificial homes made from wood or high density polystyrene, and designed to replicate the natural bee nest conditions found in a hollow tree. Hives come in a great variety of shapes and sizes, but chose your type carefully, you won't be able to change it easily if you decide later that you have made a poor choice. Using a type popular with local beekeepers makes for easy beekeeping. Use the Bee Hives page for more info on hives.

Where is home? - by nature honeybees geo-locate on the geographical position of the hive entrance, very accurately. When they emerge from the hive for the very first time they will fly round and round in ever increasing circles upwards until they have a fix on the exact position of the hive entrance. Should you move the hive a meter from its original site, next time they come out to fly they may never find it again even if it is right beside them, and you will risk losing them all. Moving a colony of bees a short distance has to be done slowly in small stages over days. For greater distances it has to be carried out at night when they are all inside the hive, and then the minimum distance you should move them is 3 miles so they are forced to re-orientate and not return to their original site.

Moving a Colony of Bees - The rule of thumb is no more than 3 feet (just short of a meter), and no less than 3 miles (5 km)!

Choosing a site - keeping in mind that once you have put bees into a hive and moving it to a new location isn't so simple, some forethought has to be given to where your hives are going to be sited. Considering the forage potential of the area is the first step in locating your apiary, along with the varying extremes of weather conditions we experience in Scotland. To give the bees the best chance chose a location that has easy access, is secure (hive thefts are not unheard of), an aspect that enjoys full sun (this is especially important in winter months), is sheltered from prevailing winds especially winter gales, is not prone to drifting snow, is dry and well drained, is well away from public areas, is not under the shade of trees, and is not going to be knocked over by livestock.

Keeping the balance - consider the local competition (think food webs and natures balance), our honeybees are not the only or most important pollinators in nature, there are many more animals including over 1500 different insect species that pollinate and feed from the wide range of flowering plants found throughout our countryside, not forgetting the fields of flowering crop species such as field beans, phacelia, oil seed rape etc which appear annually in rotation over thousands of acres of farm land. A single colony of bees can include over 30,000 foragers during the growing season, which will interact with and impact on the resident native pollinator species which make up the natural balance of the surrounding areas' biodiversity, all things biological and non-biological working in constant balance. This is the balance of nature, it's easily tipped and is already under relentless pressure from pollution, pesticides and habitat loss. Saturating an area with honeybees has a detrimental effect on the population dynamics of all native species involved, overcoming the natural competition for food resources simply by weight of numbers resulting in casualties, most of which are unseen. At a time when we have already lost over 50% of our islands biodiversity and have the dubious accolade of leading the world in species loss, beekeepers should not contribute further to the loss through irresponsible apiary practice. Not only are the local competition species affected by this but also the health of your own colonies if their numbers don't match the available food resources across the seasons. If your bees are struggling for food then so is the local biodiversity. Choosing an apiary site requires a bit of thought and consideration!

Working at height! - hives are best raised up off the ground to avoid dampness and to discourage pests and vermin. Stands can be easily made to support one or more hives, but don’t forget that once there are bees and honey in the hive it will weigh a significant amount so the stand has to be strong enough, and you will have to lift and carry at least some of it (a super full of honey can weigh over 30lbs / 13.5kg). There should be enough room between hives to enable manipulations and to discourage bees drifting from one hive to another.

Something To Eat (and drink!)

Honeybees need a wide range of pollen, nectar, water, and resin all year round to ensure their health and success. Gardens, amenity areas, scrub land, mature woodlands, wild flower areas and heather moorland will provide this, whereas intensively farmed land may lack mature hedgerows or significant woodlands and may not provide year round sustenance. Urban honeybees can fare just as well and possible better than those in the countryside due to the wide variety of garden shrubs and flowers available.

Taking rainwater from a garden container, they will drink from any convenient source nearby and are not too fussy about the quality!

You may have thought that honeybees would hibernate, but they don’t. Instead they will become quite torpid during the worst of the winter weather but on a sunny day in the middle of winter they will be seen coming out to defecate and to collect from winter flowering plants like Ivy (Hedera helix spp.) Gorse (Ulex europaeus spp.), Snowdrops (Galanthius spp.) Hellebores (Helleborous spp.) and crocus (Crocus spp.) in the early spring. It is not unusual to see bees flying out when there is snow on the ground and the temperatures are freezing!

Some forethought to what grows where and when in the area will go a long way towards keeping healthy colonies. Beware of intensely farmed areas where there may be low diversity, heavily trimmed hedgerows, vast fields of just one plant type (oil seed rape, beans, peas for instance) and where pesticides are used directly on fields or in seed treatments. They can produce masses of nectar for a short period but may have drastic effects on your colonies. Remember that your bees will fly two miles or more to forage. Check the area out for foraging potential throughout the year.

Naturally food becomes scarcer in winter months but honeybees have that covered by storing honey and pollen in the nest to sustain them during these times. Feeding up for winter to ensure sufficient stores to see them through even the worst weather can be also done artificially during the autumn and winter months (more on that in the Winter Management pages).

Equipment

Its true beekeepers never have enough equipment, and there's no end to the gadgets available, some very good and others not so much! Please refer to the Equipment pages for full details on what equipment you will need and how to use it. Beyond the hives, you'll need a bee suit - get a decent one it will last you for years and years, and gloves, and welly boots. Tools - you don’t need a lot of tools, a carry box for basics, cover screens, a smoker, a hive tool for prizing the hive components apart and for removing frames, a small hammer and nails for repairing hive boxes and frames.

Try the Beekeeping Basics Quiz

About the 'My Beekeeping Kit' website.

Contact Iain Dewar for enquiries, suggestions, corrections and contributions for improving the notes. Always welcome!